- July 29, 1848

Young Ireland was a political and cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform.

Grouped around the Dublin weekly The Nation, it took issue with the compromises and clericalism of the larger national movement, Daniel O’Connell’s Repeal Association, from which it seceded in 1847.

Despairing, in the face of the Great Famine, of any other course, in 1848 Young Irelanders attempted an insurrection. Following the arrest and the exile of most of their leading figures, the movement split between those who carried the commitment to “physical force” forward into the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and those who sought to build a “League of North and South” linking an independent Irish parliamentary party to tenant agitation for land reform.

1848 Uprising

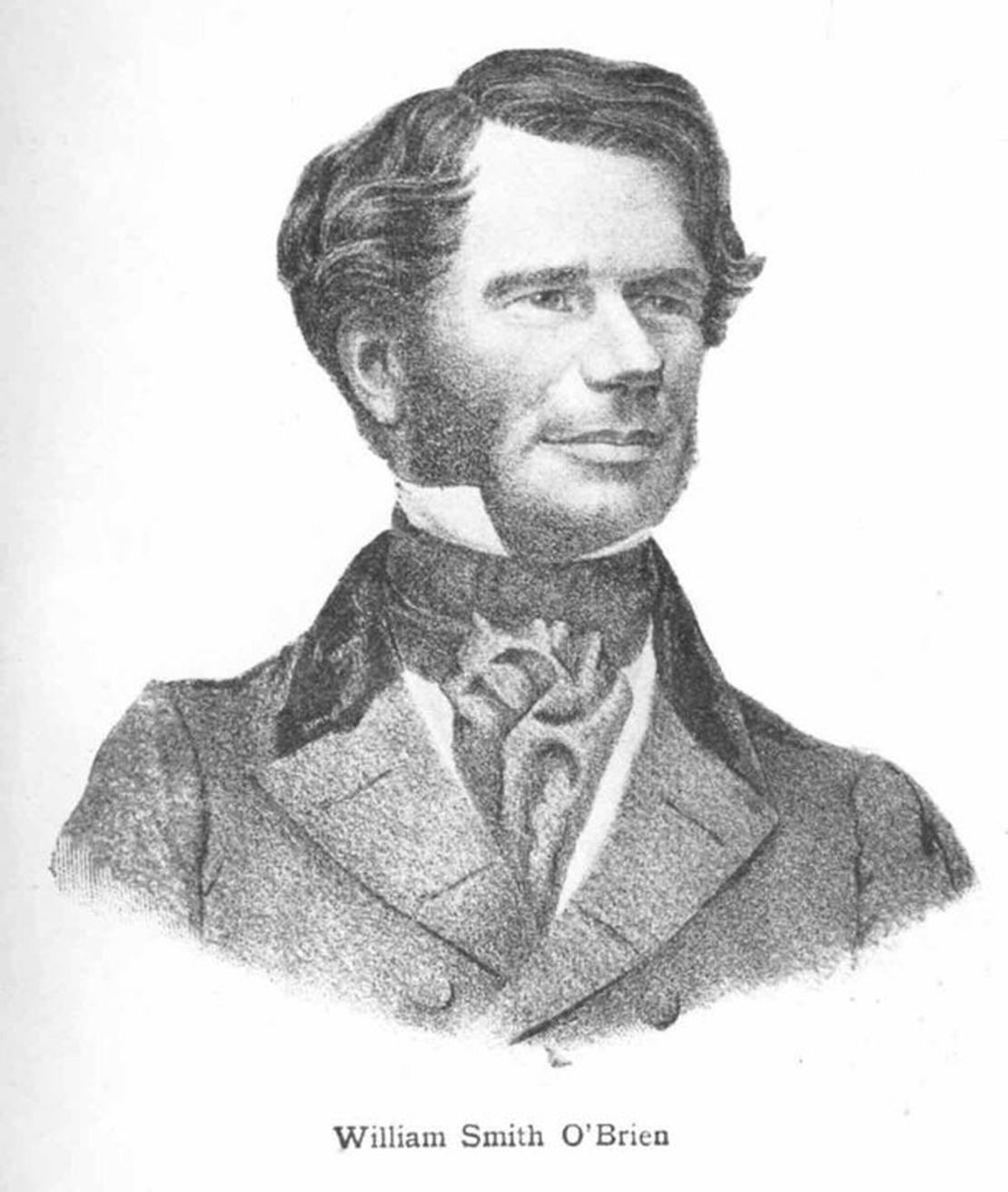

Planning for an insurrection had already advanced. Mitchel, although the first to call for action, had scoffed at the necessity for systematic preparation. O’Brien, to Duffy’s surprise, attempted the task.

In March he had returned from a visit to revolutionary Paris with hopes of French assistance. (Among the leading republicans in France, Ledru-Rollin had been loud in his declaration of French support for the Irish cause).

There was also talk of an Irish-American brigade and of a Chartist diversion in England(Allied with the Chartists, the Confederation had a relatively strong organised presence in Liverpool, Manchester and Salford).

With Duffy’s arrest, it was left to O’Brien to confront the reality of the Confederates’ domestic isolation.

Having with Meagher and Dillon gathered a small group of both landowners and tenants, on 23 July O’Brien raised the standard or revolt in Kilkenny.

This was a tricolour he had brought back from France, its colours (green for Catholics, orange for Protestants) intended to symbolise the United Irish republican ideal.

With Old Ireland and rural priesthood against them, the Confederates had no organised support in the countryside.

Active membership was confined to the garrisoned towns. As O’Brien proceeded into Tipperary he was greeted by curious crowds, but found himself in command of only a few hundred ill-clad largely unarmed men. T

hey scattered after their first skirmish with the constabulary, derisively referred to by The Times of London as “Battle of Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch”.

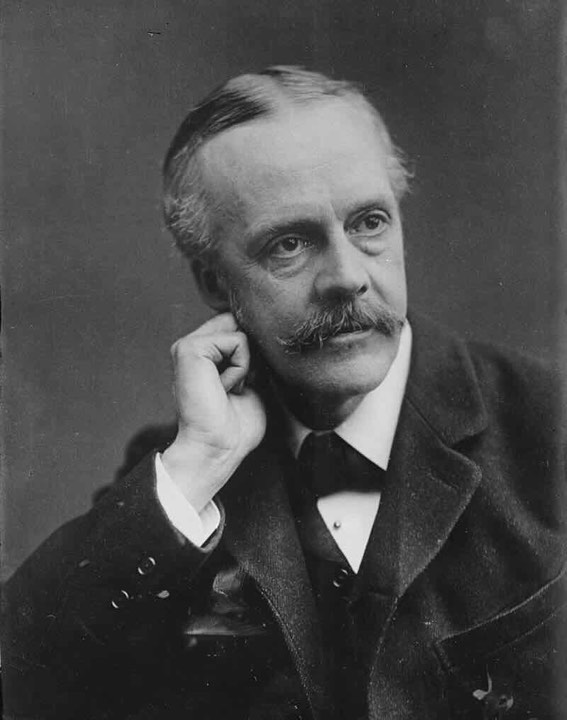

← Arthur James Balfour, born

← Arthur James Balfour, born

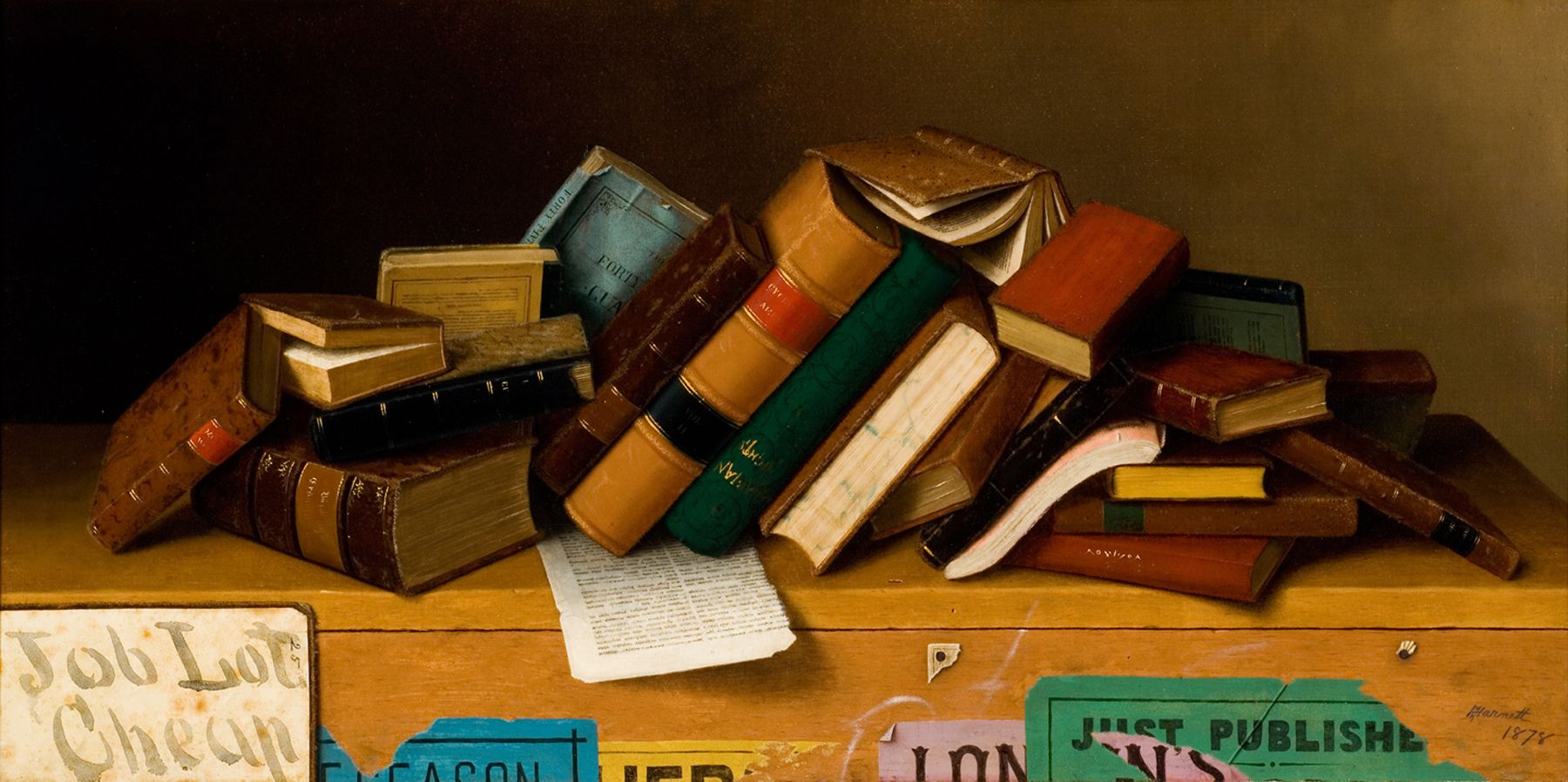

Birth in Clonakilty of William Hartnett, master of still life painting →

Birth in Clonakilty of William Hartnett, master of still life painting →