On July 14, 1404 in Celtic History

Treaty between owain glyndŵr and france

Owain Glyndŵr, sometimes anglicised as Owen Glendower (1359 - 1416) and crowned as Owain IV of Wales, was the last Welshman to hold the title Prince of Wales. He instigated an ultimately unsuccessful revolt against English rule of Wales.

Owain Glyndŵr was a descendant of the princes of Powys from his father Gruffydd: Fychan II, Hereditary Tywysog of Powys Fadog and Lord of Glyndyfrdwy, and of those of Deheubarth through his mother Elen ferch Tomas ap Llywelyn.

On September 16, 1400, Owain Glyndŵr instigated the Welsh Revolt against the rule of Henry IV of England. Although initially successful, the uprising was eventually put down - Glyndŵr was last seen in 1412 and was never captured.

In 1404, Owain captured and garrisoned the great western castles of Harlech and Aberystwyth. Anxious to demonstrate his seriousness as a ruler, he held court at Harlech and appointed the devious and brilliant Gruffydd: Yonge as his chancellor.

Soon afterwards he called his first Parliament (or more properly a Cynulliad or gathering) of all Wales at Machynlleth where he was crowned Owain IV of Wales and announced his national programme. He declared his vision of an independent Welsh state with a parliament and separate Welsh church.

There would be two national universities (one in the South and one in the North) and return to the traditional law of Hywel Dda. Senior Churchmen and important members of society flowed to his banner. English resistance was reduced to a few isolated castles, walled towns, and fortified manors.

Tripartite indenture and The Year of the French

Owain demonstrated his new status by negotiating the Tripartite Indenture with Edmund Mortimer and the Earl of Northumberland. The Indenture agreed to divide England and Wales between them. Wales would extend as far as the rivers Severn and Mersey including most of Cheshire, Shropshire, and Herefordshire.

The Mortimer Lords of March would take all of southern and western England and Thomas Percy, the Earl of Northumberland, would take the north of England. Most historians have dismissed the Indenture as a flight of fantasy.

However, it must be remembered that in early 1404 things still looked positive for Owain. Local English communities in Shropshire, Herefordshire and Montgomeryshire had ceased active resistance and were making their own treaties with the rebels. It was rumoured that old allies of Richard II were sending money and arms to the Welsh and the Cistercians and Franciscans were funneling funds to support the rebellion.

Furthermore, the Percy rebellion was still viable; even after the defeat of the Percy Archbishop Scope in May. In fact the Percy rebellion was not to end until 1408 when the Sheriff of Yorkshire defeated Henry Percy Earl of Northumberland at Bramham Moor. Thus, far from a flight of fantasy, Owain was capitalizing on the political situation to make the best deal he possibly could.

Things were improving on the international front too. Although negotiations with the Scots and the Lords of Ireland were unsuccessful, Owain had reasons to hope that the French and Bretons might be more welcoming. Quickly Owain dispatched Yonge and his brother-in-law, John Hanmer, to France to negotiate a treaty with the French. The result was a formal treaty that promised French aid to Owain and the Welsh. The immediate effect seems to have been that joint Welsh and Franco-Breton forces attacked and laid siege to Kidwelly Castle. The Welsh could also count on semi-official fraternal aid from their fellow Celts in the then independent Brittany and Scotland. Scots and French privateers were operating around Wales throughout Owain’s war.

Scots ships had raided English settlements on the Llyn Peninsula in 1400 and 1401. In 1403 a Breton squadron defeated the English in the Channel and devastated Jersey, Guernsey and Plymouth while the French made a landing on the Isle of Wight. By 1404 they were raiding the coast of England, with Welsh troops on board, setting fire to Dartmouth and devastating the coasts of Devonshire.

1405 was the Year of the French in Wales. On the continent the French pressed the English as the French army invaded English Aquitaine. Simultaneously, the French landed in force at Milford Haven in West Wales.

They had left Brest in July with more than twenty-eight hundred knights and men-at-arms led by Jean de Rieux, the Marshall of France. Unfortunately, they had not been provided with sufficient fresh water and many horses had died. They also brought modern siege equipment.

Joined by Owain’s forces they marched inland and took the town of Haverfordwest but failed to take the castle. They then moved on and retook Carmarthen and laid siege to Tenby.

What happened next is something of a mystery. The Franco-Welsh force marched across South Wales (according to local tradition) and invaded England. They marched through Herefordshire and into the Midlands. They finally met the English outside Worcester at the ancient British hill fort of Woodbury Hill. The armies viewed each other without any action for eight days. Then, for reasons that have never been clear, both sides withdrew. The Welsh and French withdrew back through Wales into the West. More French were to arrive as the year went on but the high-point of French involvement had passed.

Related Content

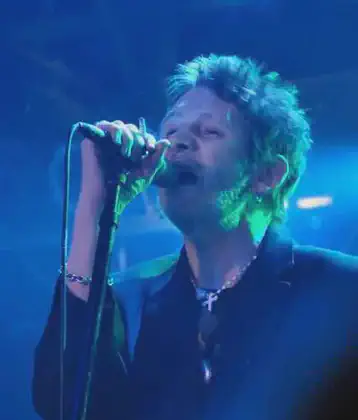

Shane Patrick Lysaght MacGowan, lead singer of the Pogues, died

Shane Patrick Lysaght MacGowan is an Irish-English musician and songwriter, best known as the lead singer and songwriter of the punk band The Pogues.

Read More

St Machar Day, patron saint of Aberdeen

Saint Machar is the Diocesan Patron Saint of Aberdeen; the Feast Day being observed on 12th November.

Read More

Oíche Shamhna - Cetlic New Year Eve (Halloween)

In Scotland and Ireland, Halloween is known as Oíche Shamhna, while in Wales it is Nos Calan Gaeaf, the eve of the winters calend, or first. With the rise of Christianity, Samhain...

Read More

ALBAN ELFED (Welsh Bardic name for autumn equinox)

Alban Elued, The Light of the Water, the first day of Autumn, was also called Harvesthome. Observed on September 21, the Autumnal Equinox was the day when the sun again began to...

Read More

Feast day of St. James

Guinness St. James Gate Since mediaeval times, Dubliners held an annual drinking festival in the Saint’s honor. Fittingly, Guinness chose St. James’ Gate as the site for their...

Read More

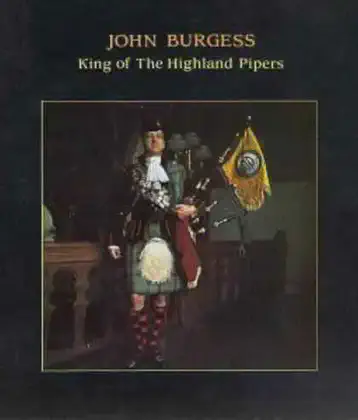

John Davie Burgess, King of the Highland Pipers, died at age 71.

John Burgess died on June 29, 2005 at the age of 71.

Read More

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified