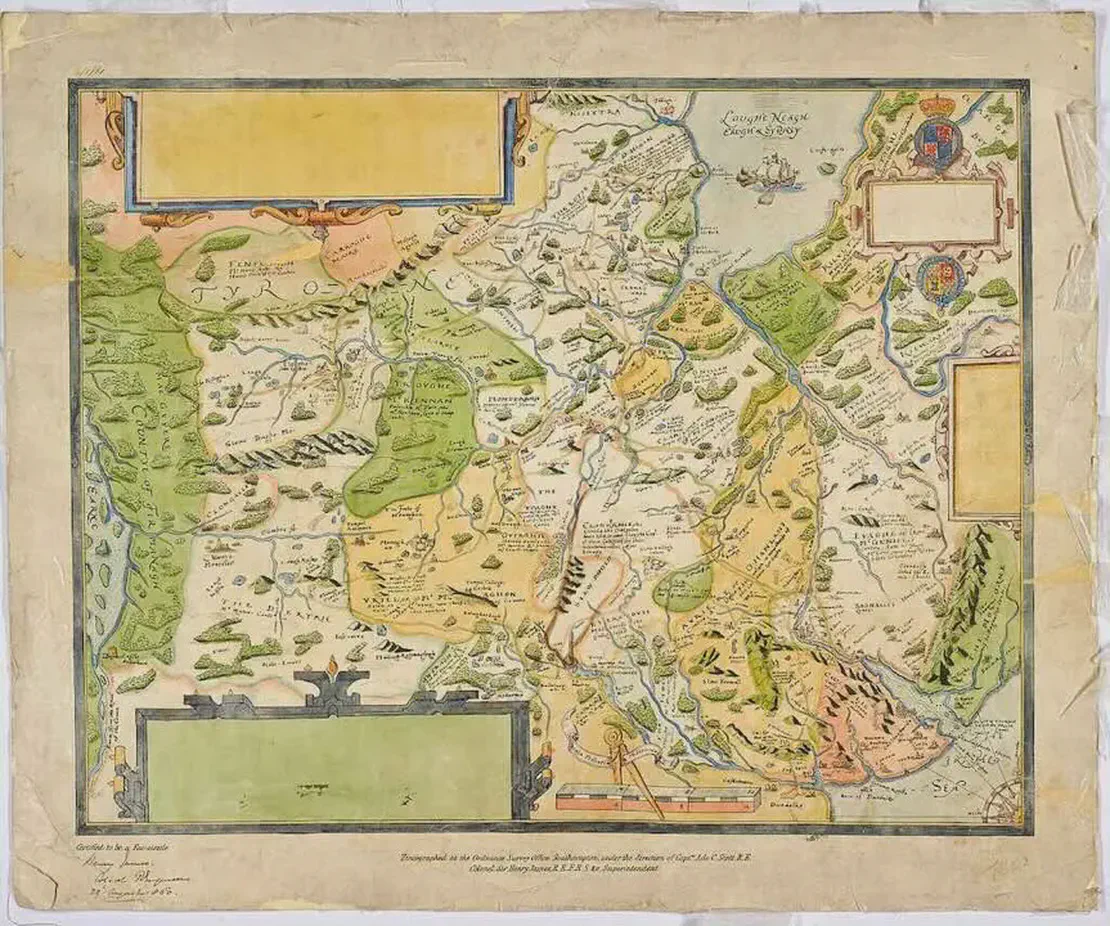

On July 19, 1608 in Celtic History

Plantation of ulster commences

The Plantation of Ulster was the organized colonization (plantation) of Ulster – a province of Ireland – by people from Great Britain during the reign of King James I. Most of the settlers (or planters) came from southern Scotland and northern England; their culture differed from that of the native Irish.

Small privately funded plantations by wealthy landowners began in 1606, while the official plantation began in 1609. Most of the colonized land had been confiscated from the native Gaelic chiefs, several of whom had fled Ireland for mainland Europe in 1607 following the Nine Years’ War against English rule.

The official plantation comprised an estimated half a million acres (2,000 km2) of arable land in counties Armagh, Cavan, Fermanagh, Tyrone, Donegal, and Londonderry.

Land in counties Antrim, Down, and Monaghan was privately colonized with the king’s support.

Among those involved in planning and overseeing the plantation were King James, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Arthur Chichester, and the Attorney-General for Ireland, John Davies.

They saw the plantation as a means of controlling, anglicising, and “civilising” Ulster. The province was almost wholly Gaelic, Catholic, and rural and had been the region most resistant to English control. The plantation was also meant to sever Gaelic Ulster’s links with the Gaelic Highlands of Scotland.

The colonists (or “British tenants”) were required to be English-speaking, Protestant, and loyal to the king. Some of the undertakers and settlers, however, were Catholic.

The Scottish settlers were mostly Presbyterian Lowlanders and the English mostly Anglicans. Although some “loyal” natives were granted land, the native Irish reaction to the plantation was generally hostile, and native writers bewailed what they saw as the decline of Gaelic society and the influx of foreigners.

Six counties

Six counties were involved in the official plantation – Donegal, Londonderry, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan and Armagh. In the two officially unplanted counties of Antrim and Down, substantial Presbyterian Scots settlement had been underway since 1606

Failures

The plantation was a mixed success from the point of view of the settlers. About the time the Plantation of Ulster was planned, the Virginia Plantation at Jamestown in 1607 started. The London guilds planning to fund the Plantation of Ulster switched and backed the London Virginia Company instead. Many British Protestant settlers went to Virginia or New England in America rather than to Ulster.

By the 1630s, there were 20,000 adult male British settlers in Ulster, which meant that the total settler population could have been as high as 80,000. They formed local majorities of the population in the Finn and Foyle valleys (around modern County Londonderry and east Donegal), in north Armagh and in east Tyrone. Moreover, the unofficial settlements in Antrim and Down were thriving. The settler population grew rapidly, as just under half of the planters were women.

The attempted conversion of the Irish to Protestantism was generally a failure. One problem was language difference. The Protestant clerics imported were usually all monoglot English speakers, whereas the native population were usually monoglot Irish speakers. However, ministers chosen to serve in the plantation were required to take a course in the Irish language before ordination, and nearly 10% of those who took up their preferments spoke it fluently.

Nevertheless, conversion was rare, despite the fact that, after 1621, Gaelic Irish natives could be officially classed as British if they converted to Protestantism. Of those Catholics who did convert to Protestantism, many made their choice for social and political reasons.

The reaction of the native Irish to the plantation was generally hostile. Chichester wrote in 1610 that the native Irish in Ulster were “generally discontented, and repine greatly at their fortunes, and the small quantity of land left to them”. That same year, English army officer Toby Caulfield wrote that “there is not a more discontented people in Christendom” than the Ulster Irish. Irish Gaelic writers bewailed the plantation.

In an entry for the year 1608, the Annals of the Four Masters states that the land was “taken from the Irish” and given “to foreign tribes”, and that Irish chiefs were “banished into other countries where most of them died”. Likewise, an early 17th-century poem by the Irish bard Lochlann Óg Ó Dálaigh laments the plantation, the displacement of the native Irish, and the decline of Gaelic culture.

It asks “Where have the Gaels gone?”, adding “We have in their stead an arrogant, impure crowd, of foreigners’ blood”.

Related Content

Shane Patrick Lysaght MacGowan, lead singer of the Pogues, died

Shane Patrick Lysaght MacGowan is an Irish-English musician and songwriter, best known as the lead singer and songwriter of the punk band The Pogues.

Read More

St Machar Day, patron saint of Aberdeen

Saint Machar is the Diocesan Patron Saint of Aberdeen; the Feast Day being observed on 12th November.

Read More

Oíche Shamhna - Cetlic New Year Eve (Halloween)

In Scotland and Ireland, Halloween is known as Oíche Shamhna, while in Wales it is Nos Calan Gaeaf, the eve of the winters calend, or first. With the rise of Christianity, Samhain...

Read More

ALBAN ELFED (Welsh Bardic name for autumn equinox)

Alban Elued, The Light of the Water, the first day of Autumn, was also called Harvesthome. Observed on September 21, the Autumnal Equinox was the day when the sun again began to...

Read More

Feast day of St. James

Guinness St. James Gate Since mediaeval times, Dubliners held an annual drinking festival in the Saint’s honor. Fittingly, Guinness chose St. James’ Gate as the site for their...

Read More

John Davie Burgess, King of the Highland Pipers, died at age 71.

John Burgess died on June 29, 2005 at the age of 71.

Read More

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified

No location specified