- July 19, 1333

Battle of Halidon Hill (July 19, 1333) was fought during the second War of Scottish Independence.

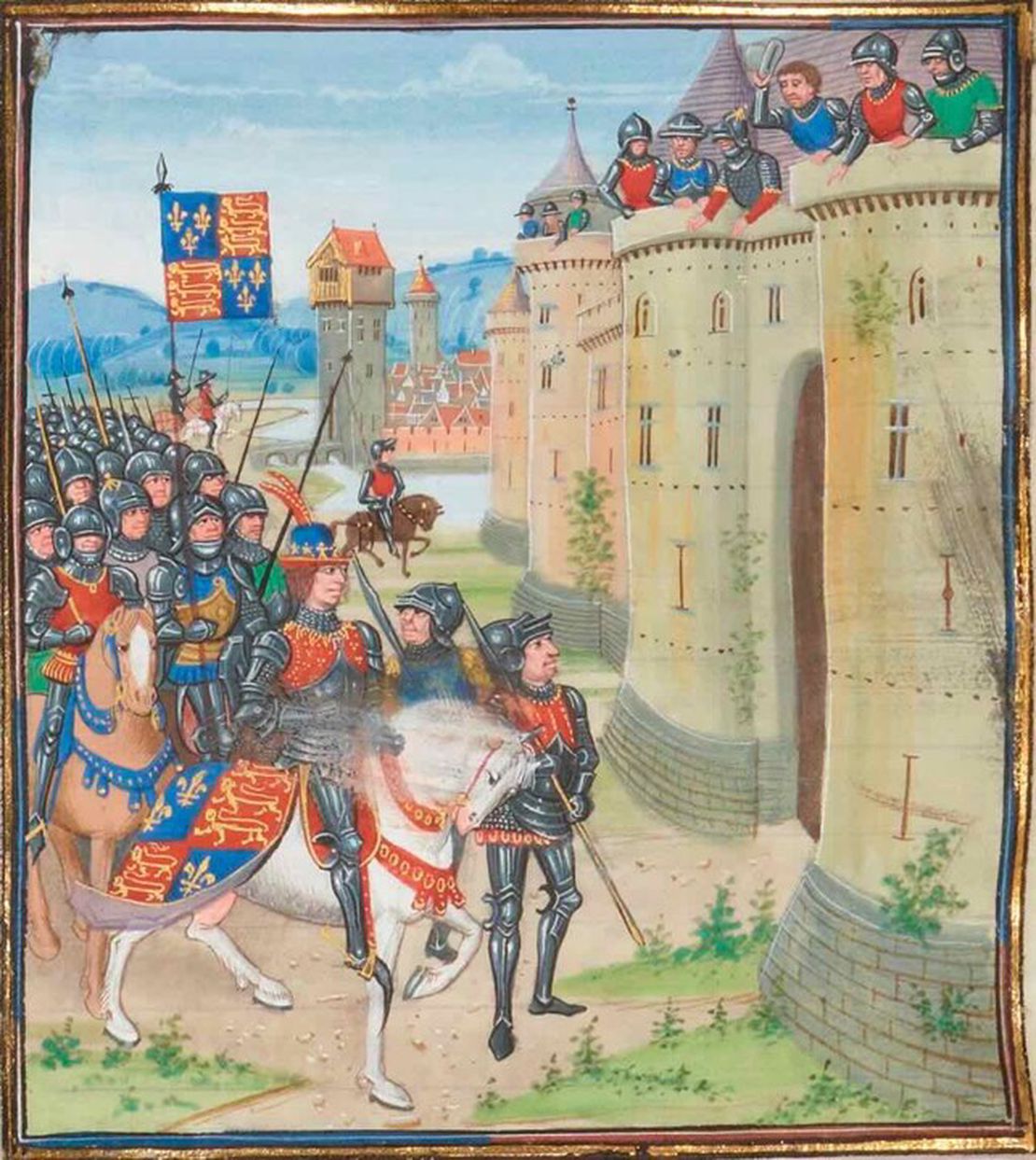

Scottish forces under Sir Archibald Douglas were heavily defeated on unfavorable terrain while trying to relieve Berwick-upon-Tweed. Douglas attacked an English army commanded by King Edward III of England (r. 1327–1377) and was heavily defeated.

The year before, Edward Balliol had seized the Scottish Crown from five-year-old David II (r. 1329–1371), surreptitiously supported by Edward III. This marked the start of the Second War of Scottish Independence. Balliol was shortly expelled from Scotland by a popular uprising, which Edward III used as a casus belli, invading Scotland in 1333. The immediate target was the strategically important border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed, which the English besieged in March.

Scots losses were nearly, 600, English losses, 14.

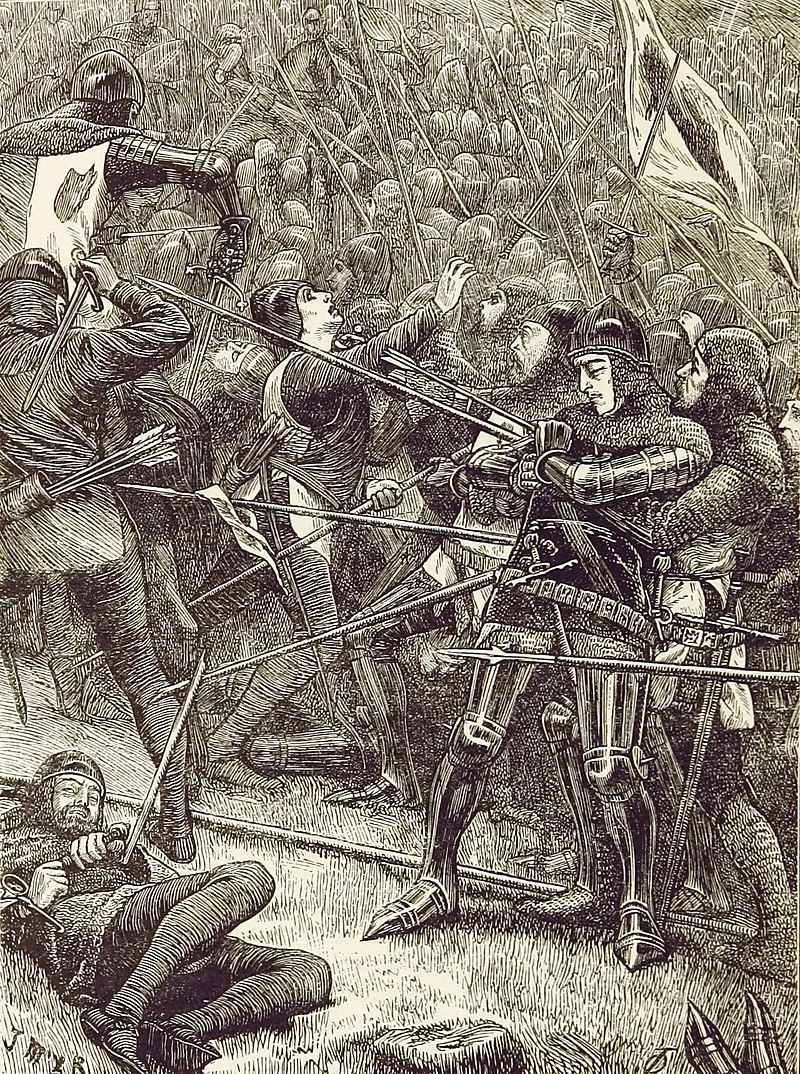

Scottish forces under Sir Archibald Douglas were heavily defeated on unfavorable terrain while trying to relieve Berwick-upon-Tweed. The battle lasted throughout July 19 but was almost entirely a slaughter of the Scottish forces.

In a reverse of the terrain at Bannockburn the Scots had to approach through boggy ground and then climb up the hill to the waiting English, they were easy targets for archers.

Sir Archibald Douglas Killed

Attacking en masse, over 500 Scottish nobles were killed including Douglas and more than 4,000 soldiers, more were killed as the English cavalry finally charged and chased the routed Scottish troops from the battlefield. English casualties were around fifteen.

Shock Waves

News of Halidon sent shock waves across southern Scotland. Edward soon received the fealty of several important landowners in the area. In England the victory, the first for many years, brought a great boost to the morale of the nation. Bannockburn had finally been avenged.

Edwards Victory at Halidon Hill was a more devastating blow to Scotland than his grandfathers at Dunbar. After Dunbar most of the nobles had been captured and lived to fight another day; after Halidon most of the country’s natural leaders were dead, and the few who remained were in hiding. Scotland was prostrate.

It was said it the time that the English victory had been so complete that it marked the final end of the northern war. For Edward did little to exploit his success; and Scottish resistance, though weak, was never fully extinguished. A great opportunity had passed never to come again.

← Battle of Dupplin near Perth in which Edward Balliol defeated the Regent, Earl of Mar.

← Battle of Dupplin near Perth in which Edward Balliol defeated the Regent, Earl of Mar.

Edinburgh Castle taken from English, reversing English encroachments against independent Scotland →

Edinburgh Castle taken from English, reversing English encroachments against independent Scotland →