On April 23, 1918 in Celtic History

A general strike takes place throughout ireland against the british governments attempts to introduce conscription

The Conscription Crisis of 1918 stemmed from a move by the British government to impose conscription (military draft) in Ireland in April 1918 during the First World War. Vigorous opposition was led by trade unions, Irish nationalist parties and Roman Catholic bishops and priests. A conscription law was passed but was never put in effect; no one in Ireland was drafted into the British Army. The proposal and backlash galvanised support for political parties which advocated Irish separatism and influenced events in the lead-up to the Irish War of Independence.

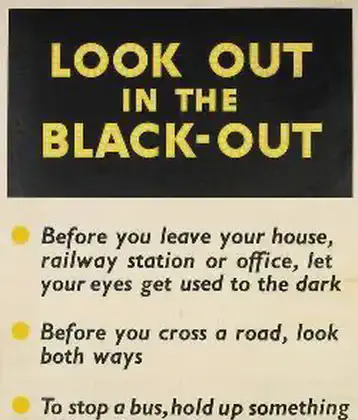

In early 1918, the British Army was dangerously short of troops for the Western Front.

Conscription in Great Britain had already been established by the Military Service Act of January 1916, which came into effect a few weeks later in March 1916.

By 1918 David Lloyd George was Prime Minister, leading a coalition government, and in addressing a very grave military situation it was decided to use a new ‘Military Service Bill’ to extend conscription to Ireland and also to older men and further groups of workers in Britain, thus reaching untapped reserves of manpower.

Although large numbers of Irishmen had willingly joined Irish regiments and divisions of the New Army at the outbreak of war in 1914, the likelihood of enforced conscription created a backlash.

This reaction was based particularly on the fact that, in a “dual policy”, Lloyd George controversially linked implementation of the Government of Ireland Act 1914 or a new Home Rule Bill (as previously recommended in March by the Irish Convention) with enactment of the Military Service Bill. This had the effect of alienating both nationalists and unionists in Ireland.

The linking of conscription and Home Rule outraged the Irish nationalist parties at Westminster, including the IPP, All-for-Ireland League and others, who walked out in protest and returned to Ireland to organise opposition.

Despite opposition from the entire Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), conscription for Ireland was voted through at Westminster, becoming part of the ‘Military Service (No. 2) Act, 1918

Although the crisis was unique to Ireland at the time, it followed similar campaigns in Australia (1916–17) and Canada (1917). In Australia, Irish Catholics mostly opposed conscription; in Canada (and the US), Irish Catholics supported conscription.

On 18 April 1918, acting on a resolution of Dublin Corporation, the Lord Mayor of Dublin (Laurence O’Neill) held a conference at the Mansion House, Dublin. The Irish Anti-Conscription Committee was convened to devise plans to resist conscription, and represented different sections of nationalist opinion: John Dillon and Joseph Devlin for the Irish Parliamentary Party, Éamon de Valera and Arthur Griffith for Sinn Féin, William O’Brien and Timothy Michael Healy for the All-for-Ireland Party and Michael Egan, Thomas Johnson and William O’Brien representing Labour and the trade unions

Following their representation at the Mansion House, the labour movement made its own immediate and distinctive contribution to the anti-conscription campaign.

A one-day general strike was called in protest, and on 23 April 1918, work was stopped in railways, docks, factories, mills, theatres, cinemas, trams, public services, shipyards, newspapers, shops, and even Government munitions factories.

The strike was described as “complete and entire, an unprecedented event outside the continental countries”